The Pitfalls of Economic Theory: A Case for Behavioural Economics

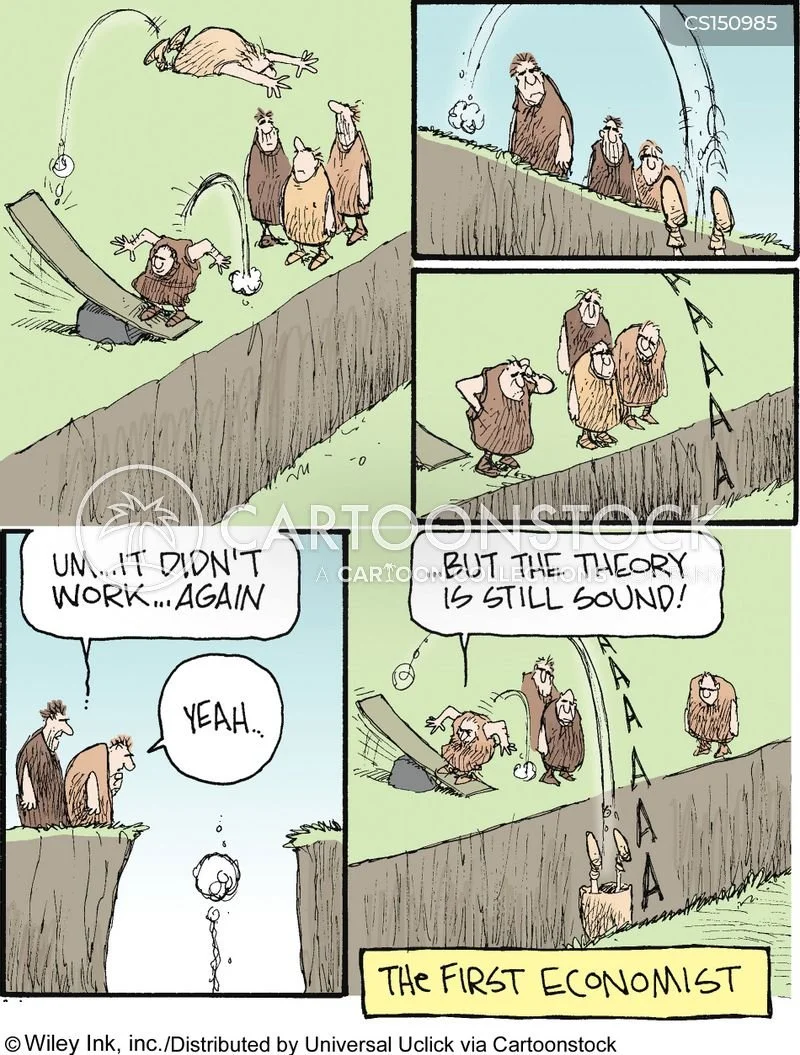

The fundamental purpose of the academic pursuit of economics is to understand how economic systems work so that economic problems can be solved effectively. Economic systems are built by societies, so effectively the discipline studies human beings. This seems obvious. But, one of the central assumptions in economic theory is that agents are self-interested, utility-maximizing individuals. This conceptualization is coined as homo economicus–the economic man. It is quite fitting honestly, as the theory of the discipline seems much more focused on the study of this ideal than that of homo sapiens. The development of this idea eventually led to rapid growth in the use of mathematical tools to explain economic theory. Economists had ‘physics envy’, where they wanted to make it seem that the work they were doing was as intellectually rigorous as the work done in the other sciences, so they used mathematics to needlessly complicate simple matters. This is not a critique of empirical research in economics and neither is it a plea to construct an entirely new set of theories. Empirical research actually provides us with a solid understanding of economic systems and many economic theories do provide a solid foundation to build on, even if they capture only a part of the picture. Rather, this is a suggestion on the power of behavioural economics, and why it should be included as part of the theoretical framework of the discipline instead of being an afterthought.

Psychology is a discipline that studies the mind and behaviour through the scientific method of experimentation. It doesn’t make any assumptions about how humans ought to act but it is more interested in observing and understanding how humans do act. Almost all of the theoretical framework of the discipline is supported by experimental evidence. Recognizing this, an effort was made to integrate this subject into economic thought. In 1974, Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky released a research article called ‘Judgement under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases’, which is credited as being the first foray into behavioural economics. In this paper, they explain that people are prone to biases that result from heuristics (mental shortcuts) in decision-making. This offers a better explanation of some of the economic decisions that people take, as it allows for human beings to be more nuanced individuals rather than utility-maximizing machines.

Based on heuristics in decision-making, Herbert A. Simon came up with the concept of bounded rationality, a contrast to traditional rationality assumed in economic theory. The idea is that decision-making is bounded by the difficulty of the problem, the cognitive capability of the mind, and the time available. He says that rather than striving for an optimal solution, people tend to strive for a satisfactory solution. Later, Huw Dixon formalized this idea by constructing a mathematical framework of epsilon-optimization, which states that an action is taken if its utility is at least epsilon close to the optimal strategy (epsilon denotes an arbitrarily small positive number). Note that this is still a rational outcome, just not necessarily optimal. This idea is almost never taught in microeconomics classes and is never considered in standard consumer choice models.

In macroeconomic theory, the economy is often modelled consisting of a set of fully rational homogenous agents, and then as a representative agent is used to depict all consumers in the economy. A central assumption in these models is that of rational expectations. It outlines how an agent’s expectation of future values is correct, on average, over time, given the information that they have. However, multiple studies in psychology have shown that people are extremely bad at predicting outcomes based on the information that they have. In the aforementioned paper by Kahneman and Tversky, the researchers describe a study where participants’ evaluation of the probability of whether a particular individual is an engineer or a lawyer was affected by irrelevant information, even after participants knew the true probabilities. Neil Weinstein studied 258 college students and made them estimate how much their own chances of experiencing 42 different events differed from their classmates. He found that they rated their own chances to be above average for positive events and below average for negative events; despite having no knowledge of what this average is. The idea fundamentally reverts back to biases that result from heuristics in prediction. Standard macroeconomic models should do away with the assumption of homogenous agents with rational expectations, and even basic models should evolve to consider heterogenous agents that predict based on heuristics.

The ideas I have conveyed here might be seen as an attempt to make economic theory more complicated. But this is necessary, as economic systems are inherently complex. My point is not to strip away all the theoretical foundations of the subject, but rather to find a way to integrate psychological explanations into even the basic models, so as to get a much better understanding of what and whom we are primarily trying to understand.

Edited by Clara Goddard & Lalia Katchelewa