One Year from the Invasion: A look at Russia’s Economy

The first response to Russia's attack against Ukraine was an aggressive raft of sanctions designed to cut Russia off and isolate it from the global financial system. Still, data coming from Russia shows that these punitive measures did not destroy its economy. Even though their economy was hit pretty hard in the second quarter of last year, they’ve stabilized very quickly. Interestingly, close to the end of 2022, it looked like Russia would recover. It is estimated that the GDP fell by around 2.5%, much less than some estimates made at the beginning of the war, which were about 10%. However, the second year is bound to be a very different scenario.

As a result of the war, some sectors were hit particularly hard, especially those dependent on imports, such as motor vehicles, where production plummeted by 60%. Consumer goods sectors were also not spared by the rising prices and increasing saving behavior from households amid the increase in uncertainty. However, these developments should not be overgeneralized. The predicted collapse was avoided since the economy turned out to be pretty resilient. Russia spent some time since the Crimean annexation in 2013 to sanction-proof its economy: they fortified their balance sheet, the external corporate debt fell, and the Putin government came into this war with very low public debt. Thus, sanctions did not have the intended impact on some parts of the economy. As the government was not under immediate pressure to issue debt, the denial of access to international capital markets had no immediate impact. It is safe to say that sanctions did not cause much short-term pain, but the effects are indeed prolonged.

Furthermore, Russia was better able to adapt contrary to expectations; import substitution schemes which took time to come through, proved to be working as they increased the manufacturing of some products. Even though Russia could not replace the imports of western technology, they could completely reorient their trade, with some lack of infrastructure capability, increasing volume with China, Turkey, and UAE. Another critical part that kept Russia afloat was the energy sector. Their energy sector was not under any sanctions for most of 2022; hence, they could benefit from high commodity prices, particularly oil, and gas. This increased Russia’s current account surplus, which is essential for maintaining financial stability.

Nevertheless, 2022 does not set the tone for 2023. This year is going to be challenging for Russia. Their oil sector is being targeted proactively by a new set of sanctions effective since December; they are also dealing with low natural gas prices (the lowest since before the war). Commodity prices are down and export volumes are down this year. This has already started to show up in the budget in current account numbers. Russia’s budget deficit is rising fast, and its current account surplus is shrinking quickly. When assessing these implications, Russia’s fiscal position comes into mind, but its fiscal deficit can be serviced domestically. More important is their current account position because they cannot generate enough private capital inflows to sustain a current account deficit. Even with their fortified finances, most of their central bank reserves are frozen, so there is a limit on how much Russia’s current account surplus can fall. This might trigger balance of payment issues and currency weakness. Meanwhile, the additional worsening effects of mobilization and people leaving Russia are harder to calculate. They are effectively lowering the GDP and putting pressure on the labor market.

Edited by William Daunais

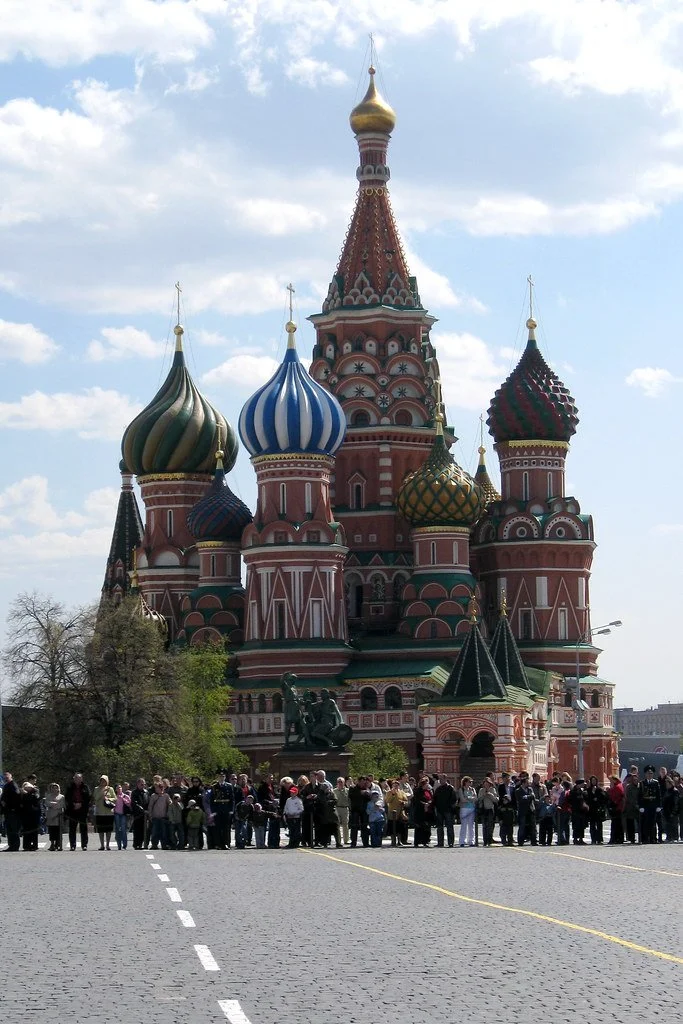

Featured Image "Russia trip, Apr 2008 - 72" by Ed Yourdon is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.