Good Money Drives Out the Bad: A Brief Survey of Gresham’s Law and a Natural Experiment in Ancient China

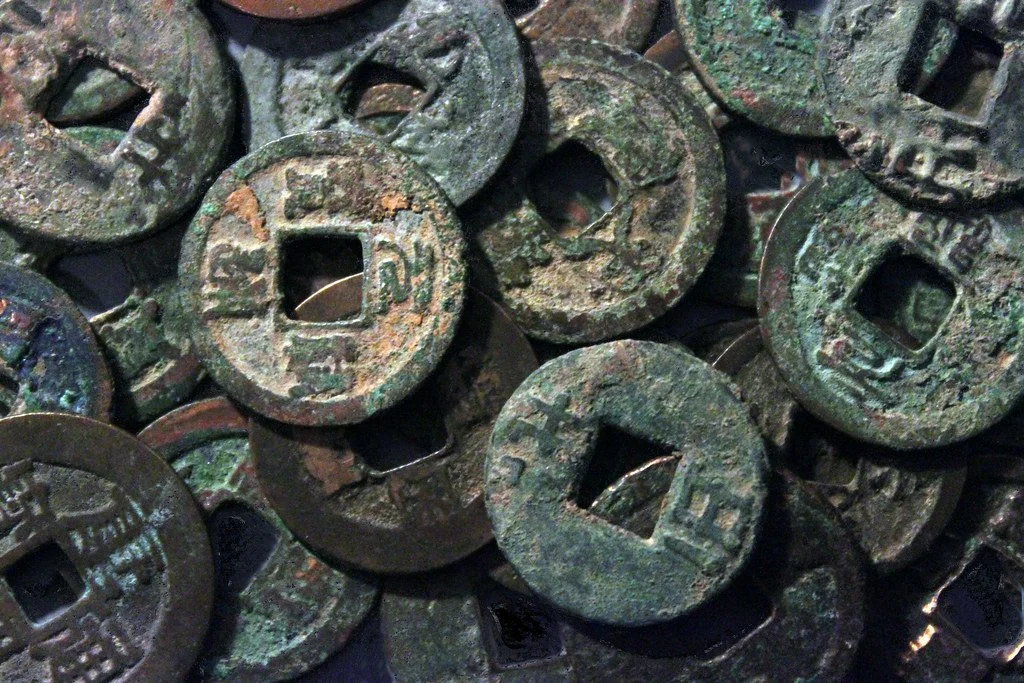

Ancient Chinese money used during the Han dynasty. The coins without thick edges are called “Ban Liang” (“半两” in Chinese). They are the very coins issued during Emperor Wen’s reign.

“Bad money drives out the good” is a widely known monetary principle. Suppose you are buying a can of Coke that is worth two dollars. In your pocket is a brand-new shiny coin and an old coin a bit worn and dirty. Though in different conditions, they are both worth two dollars. Then probably, like everyone else, you will hand the old coin to the cashier. Suppose two types of money have the same face value. In that case, people will tend to use the less valuable money but keep the valuable one. As time goes by, more valuable money will gradually disappear from circulation. This principle is known as Gresham’s law, named after Sir Tomas Gresham by Scottish economist Henry Dunning Macleod. Gresham was an English financier during the Tudor dynasty. He has observed the “bad money drives out the good” phenomenon and aided Queen Elizabeth in restoring confidence in the then-debased English currency.

The key of Gresham’s law is that the money issuer, usually the government, sets a fixed face value for a coinage. Then a bad coin, worn or counterfeit, which contains less precious metal, has the same purchasing power as the good coin. It’s not hard to understand why people tend to use bad money; they buy with bad money and save the good for themselves. And over time, the good money is driven out of circulation.

But is there some counter-example to Gresham’s law? Can good money, under certain circumstances, drive out the bad?

We shall look into a piece of history in Ancient China during the Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) to answer this question. Emperor Wen was the 5th emperor of the Han dynasty. When he came to power, the central government had limited control over localities. At the time, private minting and devaluation of copper coins were so severe that poor coins were too prevalent in the market. To change the situation, Emperor Wen implemented an innovative policy. Under the new policy, the central government didn’t mint any money. It didn’t stipulate the exchange ratio between different types of coinage. There was no legal face value for any money. Instead, the central government allowed people to mint their own money. Since the money did not have its legal face value, every type faced market competition; their value was determined by the market. To further promote such competition, the central and local governments provided weights and scales in the market, so buyers and sellers could easily distinguish the good money from the bad. As a result, the sellers would not readily accept bad money. If someone tried to pay them with bad money, they would ask for more. The buyers no longer had the incentive to use the bad money and save the good. Instead, they preferred to use good money to purchase more commodities. The good money prevailed because of fair competition and gradually drove the bad out of circulation. So, the answer to the two previous questions is: yes, there is a counter-example to Gresham’s law and good money can drive out the bad, under certain circumstances.

Emperor Wen’s policy successfully improved the quality of money circulating in the Han dynasty. Counterfeit coins ran wild for a time before the reign of Emperor Wen. Some coins contained no copper but only mud. This problem was well solved by allowing people to mint their own money. The competition would surely lead to high-quality money circulating in the market. Emperor Wen was insightful in making such a policy. None of his successors, however, continued his approach. A possible reason for this is the loss of seigniorage that occurred along with the implementation of such a policy. Seigniorage is the difference between the face value of money and the cost to produce it. When a government has the privilege to mint money, it collects a significant amount of seigniorage. By abandoning the privilege of only allowing the central government to mint money, Emperor Wen also abandoned an important source of revenue. In a sense, when Emperor Wen came to power, money debasement was so severe that he had to take a courageous move to avoid economic meltdown; a move no one else had the courage to continue. And that led to the only epoch in Chinese history when the central government denationalised money.

So, who is entitled to issue money? Economists have different answers to this question. Traditionally, it is believed that only the central government should issue money. In 1976, economist Friedrich Hayek published The Denationalisation of Money. In this book, Hayek advocates a system in which financial institutions can create private currency. Then, they compete for acceptance. Hayek assumes that competition favours the currency with the greatest stability. That is, under fair competition, good money will drive out the bad. The history mentioned provides a natural experiment to support Hayek’s theory. The denationalisation of money is economically practicable, in the past, and possibly in the future.

Edited by Nadira Anzum

Featured Image "Week 8 (2013) - 16-23 Feb - Money" by Whatknot is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0